Creedence Clearwater Revival seem to hold a special place in americana music. This is a band that set out to specifically create an amalgam of blues, rock, country, and a fake association with the deep south, with songs like ‘Born on the Bayou’, ‘Down on the Corner’, and, of course, ‘Proud Mary’. They’re almost a template for building an americana band.

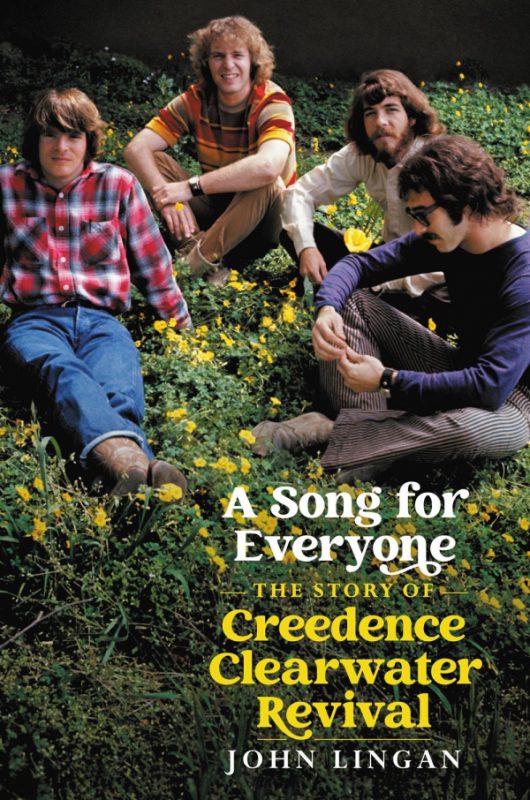

With his new biography of the band, author John Lingan has come up with a book that, finally, gives proper historical background to the rise of one of the most important roots-based bands to come out of America. There have, of course, been other books about this band, particularly Hank Bordowitz’ book ‘Bad Moon Rising: The Unofficial History of Creedence Clearwater Revival’ (1998) and, more recently, John Fogerty’s memoir, ‘Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music’ (co-written with Jimmy McDonough, 2015). ‘Bad Moon Rising’ is an enjoyable read, though it spends too much time going into the legal details of the band’s break-up and, in particular, the relationship with manager Saul Zaents, as well as John Fogerty’s estrangement from the rest of the band in general and his brother, Tom, in particular. It was based largely on interviews with Stu Cook and Doug Clifford who, at that time, still harboured quite a lot of animosity towards John Fogerty and that’s the thing that comes across most strongly in that particular book. It paints John Fogerty in a less than flattering light. Fogerty’s own book is very good and very honest. He’s known to be something of a control freak and he freely acknowledges his sometimes obsessive behaviour, but he does try to justify his approach to building the success of CCR and, while much of what he says makes perfect sense, he does try a little too hard with his justifications and this gives the book an unbalanced narrative.

John Lingan, in this frankly excellent book, has managed to tread a delicate line that makes for a much better read. He majors on the building of the band, the coming together of three friends and then the addition of an older brother, and the hard work ethic and the desire to succeed that they all shared. He sets it all against the background of the developing Vietnam War and some seismic shifts in American politics, particularly the rise of youth culture and the importance of San Francisco in the growing awareness of American youth. It’s easy to forget that CCR were a San Francisco band, so successful was John Fogerty in crafting his imagined backstory of a band forged in the swamplands of Louisiana, but they were very much of their city and directly impacted by much of the scene building there. Lingan makes good use of the fact that CCR and Sly and the Family Stone were contemporaries and he makes good use of the comparisons, and differences, between John Fogerty and Sly Stone. Lingan makes sure that you never lose sight of the fact that, whatever Fogerty tried to do to muddy the waters of the band’s origin, they were an urban outfit growing out of one of the most exciting urban environments of the time.

The author also does much to redress the attitude, prevalent at that time, that CCR wasn’t one of the frontline bands and that they were, somehow, latecomers to the scene. On the contrary, the band had been around as the Blue Velvets and then the Gollywogs (a name they hated but which was forced on them by their then manager), with the same core members, since the very end of the fifties and had been steadily building their fan base in the Bay area. They may have been considered by some to be “square”, even being referred to by some of their own fans as “the Boy Scouts of Rock and Roll”, because they weren’t part of the drug-taking Height Ashbury scene, but Lingan makes it clear that their focus was always on making the band a success and they weren’t interested in how others came by their fame and fortune and they weren’t interested in judging them, they simply had a plan of their own and resolved to stick with it. It was a plan that meant they would eventually, in 1969, outsell The Beatles in the U.S and become one of the biggest selling bands that America has ever produced. Inevitably, there was a price to pay and it all ended, comparatively swiftly given the slow climb to the top, with an acrimonious split and some bitter years to follow.

Lingan, once again, resists any temptation to slide into the recrimination that dominates Bordowitz’ book. He acknowledges John Fogerty’s obsessive nature and need to take so much on himself, but also points out that it was Fogerty’s vision that made the band a success and that all were happy enough to go along with it at the time. If anything, Fogerty’s greatest error was to forget about band dynamics and their importance as you progress. Few successful bands are democracies and there has to be a dominant figure – but they need to keep sight of the fact that the band is the gang, the pack, you can be a leader but you can’t get too far out in front and you always need to play to your strengths. Lingan’s book suggests that, had Fogerty only concerned himself with the creative side of the band, things could have gone a lot more smoothly and for a lot longer. The big failure was in also insisting on taking on the business side of the band and ending up tying them to a deal that, even in a period known for its draconian treatment of young rock bands, looks like one of the worst contracts ever signed. John Fogerty’s attitude to others in their line of work certainly didn’t help and for every good decision he took in the studio he took a bad one in the music business. Few people realise that Creedence were one of the big stars of Woodstock, but Fogerty didn’t enjoy the experience and said so and the band were dropped from the film and the soundtrack album – a decision that would have cost them dearly at the time and has had a lasting effect on their musical legacy. He also instigated the, frankly bizarre, no encore policy, believing that an encore that happened at the end of every concert had no value – another bad decision that alienated Fogerty from his bandmates and undermined their popularity with their fans. Lingan masterfully counterpoints John Fogerty’s growing control over every aspect of the band’s lives with the fragmenting of control in the society around them. As the political events of the late 1960s see the rise of the counter-culture and a more anarchic approach to life and art, Fogerty’s strict control of the band and how they performed starts to look a little like the militaristic and entitled approach to life that he decries in songs like ‘Fortunate Son’ and more at odds with the freewheeling attitude of other local bands like the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. It’s this pressure cooker atmosphere within the band that really starts the eventual break-up of CCR, which came a few years later, and Lingan documents it well. He beautifully describes events at the end of the 60s, with the rise of radical political groups and support for the Vietnam war diminishing – “Creedence were not strangers to the task of making people dance while the walls burned around them. And that’s exactly what they did to themselves….. Success had bought them nothing in terms of camaraderie or functioning friendship, and it wasn’t even a well kept secret”. And then the killer line, “A band that can’t play an encore for twenty thousand people is very obviously not having enough fun”. He records the highs and the lows so well, throughout the roller coaster ride that is CCR’s career.

What John Lingan has done with this book is restore the rightful position of Creedence Clearwater Revival as one of the great American bands. By focusing on the political background to their rise to popularity, and refusing to pay too much attention to the personal issues and internal spats that eventually brought them down, he has ensured that their music, and it’s importance to its time, is front and centre throughout the pages of what is as much social history and social commentary as it is the biography of a band. Previous books about the band have come down on one side or the other in the “whose fault was the break up” debate. With this telling of the story of Creedence Clearwater Revival, John Lingan may well have written a book for everyone.

‘A Song for Everyone: The Story of Creedence Clearwater Revival’ by John Lingan is published in the UK by Hachette Books on September 1st.

Hey Rick,

I love your stuff, but felt inclined to comment on this one … it’s been fairly widely accepted that Lingan’s book was biased against JF, and from a writer’s perspective he seemed to leave a whole lot of things ‘short’ with a lack of proper research and foundation. Hence, a lot of what you write here (and in the book) is over-simplifying a whole lot of very complicated crap which no one should (my opinion here) trivialize with broad analogies of the “times” – etc. – playing the proverbial “armchair quarterback” as they say on the states side … perhaps “the best helmsmen stand on the shore” ??

But, that said, one thing here is perfectly on-point … indeed JF did create a “template” as you say for the perfect americana band … image, songs, sounds – the whole package. He could be one of the “inventors” and probably deserves the honor, frankly.

Hi Mike – thanks for writing in on this. All critical writing is subjective but I have to say that I genuinely enjoyed John Lingan’s book and thought it did a lot to set the CCR story straight and relate it to their particular point in musical history. I found it much less critical of John Fogerty than other books on the band, even John Fogerty’s own in some ways. JF has never denied his obsessive nature and the fact that he needed to control the band’s output but, as Lingan points out and I reiterated in my review, the band were happy to go along with it at the time. It was only later in their story that the cracks start to appear. I think the comments about JF’s business decisions are fair ones and, again, Fogerty accepts, with hindsight, that he made a lot of poor decisions on behalf of the band. The good thing is that we’re discussing the book and the band and that’s exactly what you hope to get from a review. I completely agree that John Fogerty is one of the ‘inventors’ (for want of a better word) of what we call Americana music and I do think he’s a bona fide musical genius. Whatever the ins and outs of their story and eventual demise as a band they gave us some fantastic music and that’s what they’ll be remembered for.