This is the last book I received for review before I stepped down as Books Editor for Americana UK, so you’ll be reading this review after I leave.

This is the last book I received for review before I stepped down as Books Editor for Americana UK, so you’ll be reading this review after I leave.

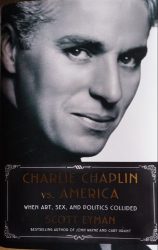

My first reaction, when I received this book, was that we should probably pass on it, because a book about Charlie Chaplin, great artist that he was, doesn’t really fit into the general remit of Americana UK. Would our readers be interested in a book about a long-gone filmmaker? But the more I thought about it, and the more I read of this fascinating book (just because I wasn’t going to review it didn’t mean I wasn’t going to read it!) the more I realised that it was a book that has considerable relevance for all aspects of the arts and for our lives today.

(At this point, I should just say that the role of Books Editor has passed to Tim Martin, who has been writing for AUK for some years and took over the Paperback Riders features series when Gordon Sharpe sadly passed away. Tim is someone who has long advocated broadening the scope of our book reviews and this would seem a fitting book to bridge the transition from my editorship to his).

Why is this book so relevant? Because it deals with conflict between the artist and the establishment and what can happen when artists look to confront social issues. Charlie Chaplin was one of the giants of Hollywood. He had a glittering career and was revered around the globe for his films that brought a great deal of enjoyment to a very wide audience. He was a pioneer when it came to the creation of commercial cinema and his influence can be seen in many recent films; you can easily argue that without Chaplin’s ‘Modern Times’ there might have been no ‘Brazil’, without his ‘Great Dictator’ there might have been no ‘Death of Stalin’. Chaplin was a visionary who believed that all art was capable of addressing the problems of modern society and he wasn’t afraid to stand up and say so. This book is largely about the consequences of doing just that and what can happen when an artist decides to challenge the establishment.

Although it covers the basic biographical facts of Charlie Chaplin’s life, ‘Charlie Chaplin vs. America’ really concentrates on his later years, when he is well established as a filmmaker and is focused on making films that go beyond the simple comedy of his early films that revolved around the brilliant creation of his “The Tramp” persona. It deals with his transition into ‘talkies’, having finally accepted that he can no longer resist the changes in the industry, and the making of his last seven films, from ‘City Lights’ in 1931 through to ‘A Countess from Hong Kong’ in 1967, including two of his strongest works from this period, ‘Modern Times’ (1936) and ‘The Great Dictator’ (1940). The dates are significant because it is during the war years, and Chaplin’s support for the campaign to open a second front in Europe, and relieve pressure on Russia, that he starts to attract the very negative attention of America’s extreme conservatives. In particular, he falls foul of Hedda Hopper, the Hollywood gossip columnist and one of the driving forces of the ‘Hollywood Blacklist’ that looked to force anyone with, often doubtful, links to communism out of the film industry. She seems to have taken a dislike to Chaplin, partly because of his sympathies for perceived socialist causes but more for his refusal to become an American citizen, which she considered ingratitude to the country that had given him so much (despite the fact that he paid all his taxes in America and employed a considerable number of American citizens), and his relationships with much younger women, which she considered immoral (despite the fact that she herself had married a man 27 years her senior). As documented in this book, she wrote repeatedly to prominent Republicans, including Richard Nixon and F.B.I Head, J, Edgar Hoover, voicing her disapproval of Chaplin and expressing her wish that he be barred from the U.S.A.

It is quite fascinating reading about the lengths some people were prepared to go to in order to get Chaplin excluded from America. It seems odd that such a relatively unassuming man (outside of his film studios) could inspire such concern in people in high places, but it’s clear that he did and to his eventual detriment. The American establishment even managed to get him saddled with a paternity order, despite blood tests proving that he could not be the child’s father. It all makes for fascinating reading.

The author, Scott Eyman, has written extensively about Hollywood, including books on John Wayne, Cary Grant, John Ford and Cecil B. DeMille as well as co-authoring books with actor Robert Wagner, and he writes with a real understanding of actors and the filmmaking process. What emerges is a story of a man defined by his early experiences of poverty and homelessness and in thrall to the talent that allowed him to escape that early life, even though it never allowed him to forget it.

In addition to his politics, America was obsessed with Chaplin’s private life. He had a string of affairs and 4 marriages, all involving women far younger than himself, but his fourth and final marriage was to Oona O’Neil and she turned out to be the love of his life. He was 54 when they married, she was just 18. It caused huge controversy and her father disowned her over the marriage – but the Chaplins would go on to have 8 children and she undoubtedly became the rock that stabilised Chaplin in later life. When he was exiled from America, she was still able to come and go as she pleased, being an American citizen, and did much to wind up his affairs in America and ensure that the bulk of his fortune wasn’t lost as a result of his exclusion from the country. Once the financial situation was properly dealt with, she would renounce her own American citizenship in protest at the way her husband had been treated. The Tramp finally found a love that he’d been missing for much of his life.

This is an extremely readable book and a fascinating account of one man’s battles against McCarthy-era America. Chaplin was never a communist and there was never any but the slightest evidence to link him with support of even socialist ethics. He described himself as a liberal and a citizen of the world, rather than of one country. Interestingly, he was a very early advocate of Freedom of Movement and abhorred borders and boundaries. Despite his attempts to prove all this to the American authorities and, despite his years of dedication in establishing the motion picture industry in Hollywood, when he left the U.S in 1952, to attend the premiere of ‘Limelight’ in London (since this was where the film was set), his re-entry visa was cancelled and he was finished in America. He never returned to work in the U.S., finally settling in Switzerland to see out his days. His last two films were produced in London and are poor representations of the talent that he was. Outside of Hollywood and his own studios, he was a fish out of water.

‘Charlie Chaplin vs. America’ is a tale for our times and something of a warning to those artists who seek to question the established order of things. But Chaplin would argue that is the nature of good art and he would, of course, be right. This is a book that has significant relevance to all of us, regardless of artistic interests. It’s also a cracking read.