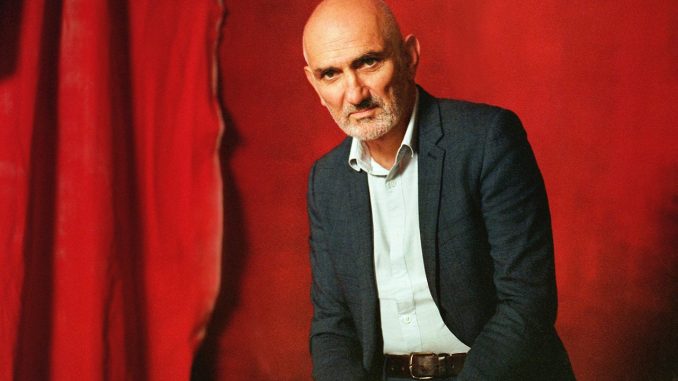

As part of our occasional series of How I Write A Song as his new Christmas album comes out, AUK talked to one of Australia’s best-known singer-songwriters, Paul Kelly.

Paul Kelly’s career now spans five decades and a huge number of different musical styles, and his latest of nearly 30 albums, ‘Paul Kelly’s Christmas Train’, has just been published. So it might come as a surprise to people to find out that even for a hugely experienced and versatile writer like Kelly, a hefty proportion of his songwriting process still consists of twiddling his thumbs, fending off tedium and as he puts it “waiting for the accident.”

“A song can start from really odd beginnings,” he tells AUK. “Most songwriting is random. I think of it being closer to fishing: you go out fishing for three or four or five days and nothing much happens, then some days – something does. But it wouldn’t have happened if you’d not gone out those three-four-five days.”

“Often the song happens when you look out the window and think about somebody else, or when you’re playing somebody else’s song and it leads you down a path. Songs happen by accident, but by saying that I’m not saying you just have to wait around for inspiration. You have to be there, waiting for the accident.”

For Kelly, songwriters need to train themselves to create the opportunities for those ‘accidents’ to take place, which is, he says, far easier said than done.

“It’s harder and harder because these days you can always distract yourself going online or looking at your phone,” he points out.

“ But writers down the ages have always had that. You sit down at the blank page and just get up or make a cup of tea or do the washing or something. You keep walking away from it. So I think the most important thing is to give myself ‘do nothing’ time and that’s a discipline in itself.”

From Kelly’s point of view, there’s no escaping that ‘do nothing’ time if you want to create. As Kelly puts it: “You’ve got to turn up. You’ve got to get to your instrument, piano or guitar and freeform until something happens. I don’t find it that enjoyable. I get bored most of the time I’m trying to write a song.”

The second key element, Kelly says, is one which all the other artists interviewed so far in this series have emphasised. That is to be sure that when you have an idea to have the self-discipline to write it down as soon as possible. Otherwise, the chances of it disappearing back down into your subconscious, probably never to emerge again, Kelly warns, are very high. The only thing that has changed to that golden rule for Kelly over the years is the format. Back in the day, he’d use a little notebook, now he’s moved on to the notes app in his phone.

As for the content, rather than the method, Kelly’s attitude is probably simplest put as “never to rule anything out.” The interview has kicked off with an invitation for him to give an opinion of a Guy Clark quote, ‘some days you write the song, some days the song writes you’ and he replies that “You think of Guy Clark and Butch Hancock, Joe Ely, Townes Van Zandt and they’re real story-tellers, yarn-spinners, the whole tall tale tradition is big down there.”

“ Texas songwriters are almost a breed of their own. I’m probably wandering off the point a little bit but they seem to come at things from a different angle, like that Joe Ely song about him and Billy the Kid never getting along, or Butch Hancock’s ‘She Never Spoke Spanish to Me’, Guy Clark finding a knife in his father’s drawer in ‘The Randall Knife’. I love that.”

“ I guess it [still] makes the point that the way into a song is anything, any way you want. There are no rules and the Texan writers show that.”

Yet there are some big underlying differences between some Texas writers’ strategies for song creation and Kelly’s approach. The inspiration for ‘The Randall Knife’, to go back to the song he mentioned, was born from Clark and his siblings grim divvying up of his father’s objects after his death: ‘They asked me what I wanted, not the law books, not the watch,’ Clark sang. ‘I need the things he’s haunted.’

But Kelly says that this deeply personal element is mostly missing from his songs: it seems like his own memories or experiences tend to be more indirect, almost sidling into his creative writings of their own accord rather than being deliberately placed there.

“Most of my songs are character-based,” he says. “I find my way into a song, imagining a character in a particular situation or imagining a particular voice and taking it from there. But there are often little things from my own life which will come in.”

He cites the case of ‘Every Fucking City’ (2000), Kelly’s hilarious account of an Australian’s European backpacker tour where his wearisomely superficial experience of a non-stop series of big cities acts as a backdrop for an off-on-off love affair. In the song, one memorably meaningless moment of this relentless Eurocity-travel happens in Dublin, where just like the backpacker, Kelly says “I’ve been in Temple Bar seeing people getting drunk in the streets and throwing up their Guinness and all that. “

”And I remember going to Ireland from the late 1980s and then over the years, seeing how that particular part of Dublin which had its own character for a while then changed and became like certain areas in certain other cities.”

“So that comes from direct, real-life observation. You can’t write anything with much truth unless you have that. But my songs aren’t autobiographical, I never felt the need to express myself fin that way.”

“ Songs to me are fiction, playing around with things. But lots of things are from my own life, like the recipe for gravy for ‘How To Make Gravy’ – which is given a makeover, 25 years on, on ‘Paul Kelly’s Christmas Train’ – “is a real one which my first father-in-law gave to me. So that’s a true thing, in a made-up song.”

Kelly reinforces this point of real-life featuring in an unreal world when AUK kind of randomly asks (full confession – they’re two personal favourites of the interviewer) about the origins of two of his much less well-known songs. ‘You’re Still Picking the Same Sore’ off ‘Wanted Man’ (1994) deals with the predicament of being stuck in the middle of an interminable, rather tedious break-up between two friends. As Kelly says, we’ve all been there and most of us have hoped (if not known quite how to express it so brilliantly as he does) that said friends will, like in the song, find themselves a boat to sail to the middle of nowhere, sort it out and stop boring everybody else in the process. “But they never did” he concludes with a wry laugh.

Then there’s ‘Anastasia Changes Her Mind’ off ‘Deeper Water’ (1995), which outlines the predicament of a gambler whose girlfriend disappears one day leaving only ‘a kiss on the mirror and a couple of condoms by the bed.’ His luck on the bets soars in her absence, something he says must have been due to ‘that kiss on the mirror, that I’d touch with my lips just for luck each time I’d go.’

Then Anastasia returns to him, and as the gambler ruefully concludes ‘Now ‘stacey’ takes the crumbs from the table, and feeds them out back to the birds. Me I can’t even pick the daily double, since that kiss on the mirror disappeared.’

Thanks to the images taken from entirely inside the house, the song becomes a kitchen-sink drama about attitudes to luck and superstition all condensed into three minutes flat , and Kelly says that ‘Anastasia Changes Her Mind’ is “a good example of how I write songs.”

“A whole lot of things ended up in it. I’m not a betting man myself, but I have friends that liked to bet. The lipstick kiss on the mirror, that’s from real life but a different situation.”

“And I remember very clearly the song title came from talking to a friend of mine who was talking about her son and his girlfriend Anastasia. I can’t remember the exact situation, whether they broke up, they might have got married. But talking about it, she says, oh ‘Anastasia always changes her mind’ and I thought that was a really good title.”

“So the song was made up but it had a whole lot of little things made their way into it. There’s a saying my mother used to say, too, ‘lucky in cards or unlucky in love,’ so that was a phrase from my childhood. And that’s right at the back of that song.”

As for what has become one of Australia’s favourite Christmas songs, ‘How To Make Gravy’, Kelly’s recipe for its creation contained more than one familiar ingredient of his own typical song-writing process. There’s the contribution from his first father-in-law, of course but there was a lot of hanging round, too, he says waiting for the accident to happen.

“It came about when I was trying to write a Christmas song, in a way it was a commission: ‘can you write this song for a charity record?’ I thought I’d have a crack at it, I remember thinking ‘I’ve been writing songs for 20 or 30 years I think every writer has to write a Christmas song.’”

“ So I set myself that task and immediately got stuck for quite a while. Then I thought ‘how do you write a song about Christmas when it’s been done so much?’ And I thought maybe the best way was ‘why don’t you write about somebody who can’t be there for Christmas?’ and then the next thought was ‘why can’t they be there for Christmas?’ and then the next thought was ‘oh, they’re in prison.’”

“Once I had that, it was like I had the key to the song and the rest happened very quickly.”

What is also special to ‘How To Make Gravy’, and perhaps helps make it even more memorable is – as Kelly said in another interview on Australian TV a few years back – structurally it doesn’t follow a lot of songwriting rules. But, he tells AUK, that wasn’t a deliberate strategy to stay in keeping with its subject of lawbreakers. “It just sort of happened like that, so when I said that, it was more in hindsight.”

“It was only the song was finished and then I could look back, I thought ‘oh well, there’s a Christmas song, it doesn’t have a chorus, it’s set in prison, it’s not very regular in terms of rhymes and meters of the words….’ So in that way I thought this song doesn’t follow that many rules.”

But there’s no getting away from the unusual (for Christmas songs) nature of where the ‘How To Make Gravy’ narrator is singing. As it happens, this is an example of another key Kelly element of his music: as he puts it: “I don’t think any song is any good unless it’s got an element of surprise about it…the crux of finding a song is being surprised.”

When it comes to the basic drive to compose, though? For some songwriters, it’s purely a means of self-expression. (To stay with the Americana songwriters and use a quote attributed to Todd Snider, ‘I didn’t write this song to change peoples’ minds, I write it to ease my own.’) At the opposite end of the scale is an inner need for the world at large to ‘get’ a song’s meaning, or for the writer the song risks losing its relevance.

Kelly, it turns out, integrates part of both those creative motivations into his songwriting.

“I think I write songs to try and solve a puzzle or I’m playing [around] with something or something that sounds good, so I’m probably writing them for me. But you don’t have to ‘get’ a song to love it. It just has to land.”

“I guess I tell if that happens when I’m playing a song, whether it’s to a couple of people in a room, or family or an audience. You can feel that landing on the listener and they have a response.“

“They might not ‘get’ the song, which I think is a very reductive way of looking at it. The best songs you keep on finding new things over time each time. I just love them, I love their combination of sound and musical notes, what’s going on, the lyrics, strange associations. But they do land on me in some way.”

As for the wry humour that often features in his music, rather than being a deliberate addition, he says, “it’s probably more my temperament. Was it Montaigne or some essayist from centuries gone past who said ‘when something bad happens to you it’s a tragedy, when it happens to someone else it’s a comedy?’”

“ I guess I see the funny side of things a lot: when I wrote ‘How to Make Gravy’ I remember when I played it to the fellow who had asked me to write a song for the Christmas charity, he was looking very sad at the end of it. And I said – ‘it’s a comedy!’ That’s how I’ve always seen it. Other people see it more as a sad song. But to me, that’s all mixed up.”

“ I love mixing up sad songs, happiness and sadness mixed together….my touchstone is Hank Williams, his songs are mostly very sad, very lonesome. But his music has a real pep in it, you can whistle the tunes.”

“I love it when the music is working against the lyrics, that contrast….Muddy Waters once said ‘sing sad songs happy and sing happy songs sad.’”

So to sum up his idea of how his songs reach people best, Kelly says it almost always depends on the context. “David Byrne writes about this really interestingly,” he says, “music works very differently in different spaces. A song that might ‘land’ in a quiet concert audience listening and being there attentive, will not work when I play it at a noisy festival or a crowded bar or a beer bar or some backyard party.”

“ It’s the setting that makes songs land. Most of the songs that I have written and continue to play and like are songs that have landed. Maybe just to four or five people I know will like it, but they land. They land.”

Paul Kelly’s Christmas Train is available now on Gawd Aggie/Cooking Vinyl available here.

Fascinating interview, thanks. Now I need to dig out “Songs From The South” again, which I bought after a previous article on Paul Kelly