If Stewart Lee is the comedian’s comedian, then Aimee Mann is the songwriter’s songwriter. The Oscar-nominated, Grammy-winning singer is a hugely observant student of human behaviour, drawing not just on her own experiences to form the characters in the songs but tales told by friends, and her new album ‘Mental Illness’ (which you can now stream in its entirety courtesy of NPR music) shows off her rich, incisive and wry melancholia in an almost all-acoustic format, with a “finger-picky” style inspired by some of her favourite 60’s and 70’s folk-rock records, augmented by strings arranged by her longtime producer, Paul Bryan. Mark Whitfield spoke to her about the new record, her feelings about the new era in US politics and what she thought about the ending of Mad Men.

If Stewart Lee is the comedian’s comedian, then Aimee Mann is the songwriter’s songwriter. The Oscar-nominated, Grammy-winning singer is a hugely observant student of human behaviour, drawing not just on her own experiences to form the characters in the songs but tales told by friends, and her new album ‘Mental Illness’ (which you can now stream in its entirety courtesy of NPR music) shows off her rich, incisive and wry melancholia in an almost all-acoustic format, with a “finger-picky” style inspired by some of her favourite 60’s and 70’s folk-rock records, augmented by strings arranged by her longtime producer, Paul Bryan. Mark Whitfield spoke to her about the new record, her feelings about the new era in US politics and what she thought about the ending of Mad Men.

The new album feels melancholic to say the least – the theme of dishonesty comes up in more than one track, and a sense of things not being what they appear to be. Has any of that fed through from world events or is it a more personal record?

You know that was kind of the backdrop but I finished it last summer so that was before the climate of outright deception and lying became our national sport (laughs). Yeah it was more personal – there was this guy that I knew and that friends of mine knew who we were all friends with and he turned out to be very deceptive, you know, lies he told and things he’d stolen and it was such a shock to encounter that. So that kind of snuck into a few songs, some of those details.

One of the things I think comes through in all your songs though is that sense of compassion for the people in them, even for the characters for themselves. Do you think that’s true and that in a subtle way it’s making people feel empathy when there’s so little of it around?

I do think it’s important to feel empathy but you know, listen I feel obviously for Trump but I still think he should get the hell out – you know I don’t feel sorry for him enough to think that he’s entitled to ruin the world for everybody. There are certain limits you have to set. Sometimes those limits are absolute and it’s like, I can’t have a relationship with this person, or I can’t allow this person to continue doing what they’re doing.

Absolutely. A lot of your tweets recently have referred to fighting back against what happened in November but you’re not particularly known for making political statements in your music. Have the events ever made you feel like writing a protest song?

Well before the election I did write a song about Trump as part of David Eggers’ 30 Days, 30 Songs, the 30 days before the election, it was a song called “Can’t You Tell”, and that’s probably as political as I get, and even that song I wrote from Trump’s point of view and tried to get into his head a little bit, or my interpretation of what might be in his head. I think I understand him but you know he’s a child, he’s a child who is very demanding and thinks the world revolves around him and that the rules don’t apply to him, and thinks he has a lot of evidence to support that so far, and I think that will be his undoing. Thank God, let’s hope. But it also makes him a very dangerous person.

Absolutely. And I think a lot of people over here are worried we appear to be aligning ourselves so closely with him as well.

Yeah you know what it is, it’s Boaty McBoatface, there’s a section of people who are like “burn it down, I don’t care, they’re all alike”, and they don’t want to think about it, they think it’s funny or they think it’s rebellious to vote for someone like this, and this is what you get. There’s a type of American who really doesn’t think about the consequences of their actions, and kind of has an entitlement problem. And an anger problem, but unearned entitlement generates a lot of unearned rage, and then this is the aftermath, these are the consequences of going through that.

I’d agree with that. Moving back to the new record, I think ‘Poor Judge’ is one of the best songs you’ve ever written, some lovely wry lyrics (“falling for you was a walk off a cliff”) and the arrangements are lovely. Can you tell me a bit more about it?

Well that was a song I co-wrote with a guy named John Roderick who was in a band called The Long Winters out of Seattle, and it’s been a long, long time since he’s written a record, I think he’s had a lot of writer’s block, that was part of the problem. So he sent this song to me which was kind of half done, and most of the music is his, like the chorus and the initial idea, and I wrote a lot of the words and the bridge to it, and I just thought it was a really beautiful song and you know it’s certainly a sentiment I’ve written a lot about, the idea of repeating mistakes (laughs) – it’s a classic. Who can’t relate to that? It’s like here I am, doing the same thing again and again. I think realising your own fallibility is heart-breaking sometimes – you can see it, you can recognise it, but you still can’t do it differently. Sometimes it’s hard to know… I mean, I do ask myself what would a normal person do? (laughs) You know the truth is the normal person probably wouldn’t be involved, they’d have run away a long time ago from the kind of people you find yourself having to make choices about.

But I guess at least there’s a self-awareness of that fallibility? Some people don’t even get to that point.

I think it’s important to have compassion for yourself. You know people don’t learn things all at once. Sometimes you have to get to the end of the road to realise it’s a dead end. I’m one of those people! I have to go all the way and see for myself, there’s no way to tell me (laughs) and it’s very frustrating for me, when other people are the same way and I try to tell them, you know from my own experience, and they don’t listen. It’s frustrating but that’s the way it is.

The album clearly has some of its roots in the folk artists of particularly the 70s, perhaps more so than any other record. Was that era of music a big influence for you?

I think definitely music from the late sixties and early seventies was an influence on me, and maybe that’s true for everybody in terms of what they were listening to when they were young, it kind of becomes the touchstone sound. I think almost more in terms of production I was looking for an influence. I mean there have been millions of acoustic records made since 1972 but I wanted to go back and hear what acoustic guitar records sounded like and how produced they were – songs that have remained for me an impression of being very sparse, I was curious to know just how sparse they were, and it is interesting, I do think as time’s gone on and Pro Tools has become the way people record records, and there’s unlimited tracks – it is very hard to restrain oneself putting on overdub after overdub. But the sparser production to me has more impact, even if you’re dealing with an acoustic guitar or softer sound, so that was more of an influence. Songwriting-wise and harmonically, all that kind of music is kind of inside me because I’ve heard it from such a young age.

You’re not an americana artist as such but your music has a lot in common with the genre, particularly the way the songs themselves are so strong, the melodies and the narrative.

I do like a well-written song, I like them to have beginnings and endings and bridges and you know sections, and have the lyrics be really considered – that’s almost more old fashioned, sort of – I really like a traditional song structure which is possibly more a nod to Cole Porter writing than anything else.

You mention Raymond Chandler as a point of reference for one of your songs but to me Raymond Carver is also in there somewhere, the way the stories don’t have dramatic beginnings or endings but are snapshots of life and very personal small decisions people make. What other writers have influenced your work?

I haven’t read that much Raymond Carver, and Raymond Chandler was specifically about one song, Patient Zero, because that’s such a specific Los Angeles song. I don’t know, I mean F. Scott Fitzgerald is one of my favourite writers, I really like language, and writers where choosing the right word makes all the difference, but I see that in comedians I like too. Whoever is a lover of language is somebody I gravitate towards.

The new video for “Patient Zero” is terrifically memorable and unique and you do have a reputation for having some of the most creative videos out there – how much involvement do you have with the storylines and production of the videos?

The last one I had a lot of involvement because the director’s a friend of mine and I can’t remember what his original idea was, I think he had an idea about somebody who gives somebody else a hermit crab, and I felt that was a really interesting image, and I remembered this movie I’d seen in the 80s called “The Dresser” and so I started to bring in elements of that, the relationship between this actor and his assistant, and I was talking to Andrew Garfield about being in the video which would have been so amazing. Because I’d written this song inspired by him, I met him at this party and then had this idea for a song and I pictured him, you know as you do, as being in this story you’re thinking about. But I got James Urbaniak and I think he’s such a great actor and with Tim did a great job; and you know I always want to make these perfect three-minute movies but videos are tough, there’s never any money or time, but I think they did a great job.

Matthew Weiner also appears in the video of course. Out of interest were you a fan of Mad Men and what did you think of the ending?

Oh yeah I loved Mad Men. I liked the ending, I thought it was great. I think the ending of a classic show is always going to cause controversy because people have expectations, and they don’t even know what they’re expecting. But I mean with the Coke commercial, this character, you know, this is his art – he is in the world of advertising and that’s the medium through which he does express ideas that he connects to. And in a way that’s sort of valid, I kind of get that. I also have a soft spot for advertising and graphic art – my father was in advertising and I definitely see how there’s an artistry to it and a craft to it when it’s done really well. I mean that Coke ad was sort of perfect… I remember seeing it as a kid and thinking it was pretty great. I’m fascinated by the ability of words and images and music to influence people, and it can be used for good or it can be used for evil.

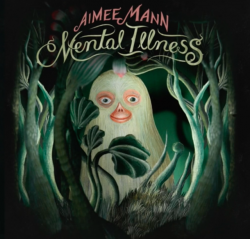

Just while we’re talking about images, I love the cover art for your new album. Is that creature on it a goose?

I don’t know. It was a piece of art I saw by an artist called Andrea Dezso, and I just thought it was perfect because it’s sort of creepy and disturbing but also sort of goofy and adorable, all at once, and that’s kind of how I feel about the record, and the topics I write about and you know, my own craziness and my friends’ craziness, and people being flawed and sad and wonderful all at once. It’s tragic and it’s funny and sweet and terrible all at once.

Finally do you have any plans for UK dates this year?

No plans yet, I have a tour coming up that ends in May and after that I’m not sure yet, it’s been a while since I’ve been there so I’d really like to come back.

Thanks very much for talking to us Aimee.

“Mental Illness” is released in the UK on 31st March 2017 on Super Ego Records.