How much great music is left in the basements and attics of houses, behind a shelf in the backroom of a disused studio, abandoned in a box of dusty LPs? How much can we salvage and how many artists will be posthumously recognised? It happened with Connie Converse years after she disappeared, and people like Nick Drake were finally seen as musical geniuses after their untimely deaths. Maybe it’s time we start looking back at who was forgotten.

Against the backdrop of the folk movement, tiny record labels across America offered aspiring musicians the chance to record and circulate their songs. If you poke around the Internet long enough, you can find scores of artists from the 60’s and 70’s who released a single LP in their life, and even more who only recorded one 7”. Thanks to the legions of vinyl fanatics who have turned rare pressings into a form of currency, we have traces of archival information on what these songs were called, and occasionally, a re-release of the music itself on streaming.

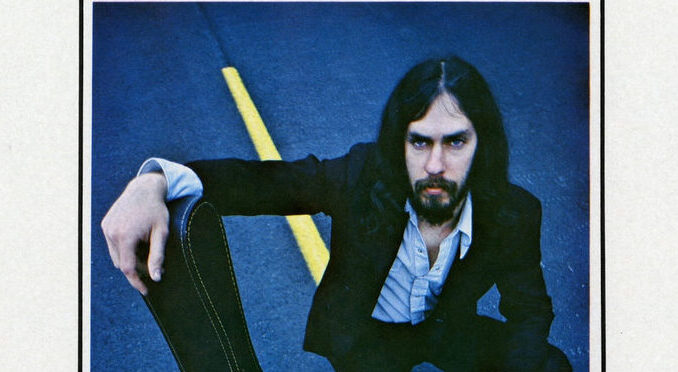

Mark Jones was one of those artists. He recorded a single album, “Snowblind Traveler”, which was released in 1979 under the label JRM, a small studio in Salem, Virginia. In 2018, the record was reissued by Numero Group, an archival record company, and put on streaming platforms. Given how obscure the record was, little information can be found about Jones himself online. All we have is a name, his photo on the album art, and the eleven tracks he wrote in a short music career.

At a little over 30 minutes, “Snowblind Traveler” grapples with working class life in America. “I am just a worker at the power plant,” Jones sings at the very beginning in ‘Harrisburg’, describing the slow deterioration of his surroundings. “They never told me things they couldn’t know / Now this town holds nothing, things that might not show for years”, suggests that both the landscape’s physical decay and workers’ health endangered by carcinogen exposure are intertwined.

Opening an album with that thesis, the plight of the American industrial worker, Jones becomes an everyman narrator throughout the record. The motifs, lyrics, and rhyming schemes throughout “Snowblind Traveler” are rudimentary, often embodying tropes of country and folk we’ve heard a thousand times elsewhere. With titles like ‘Leaving Virginia Behind’, you can pretty much guess what the story is about.

What really makes this album special is the little attention it ever received, despite paralleling the production and sound of Jones’ contemporaries that later became Americana legends. The harmonies throughout the album are just like those of Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris on 1974’s “Grievous Angel”. Thematically, Jones’ observations resemble much of Bruce Springsteen’s: ruminations on economic depression, hard times, and the urge to keep wandering for greener pastures. ‘One Way Train’ captures a Cosmic American sound with a steel guitar. “I’ve seen too many towns along the highway”, Jones sings in the last verse, agreeing to finally settle down with his love.

Perhaps his best work on the album is ‘Lion Trap’, a somber requiem of the American proletariat. The industrial decline of the 1970s and the offshoring of US steel and auto left a lot of blue collar Americans watching the places they live slowly collapse. For Jones and other workers, this meant their back-breaking labour continued without economic advancement or job security. The ‘lion trap’ remains, with Jones likening the confinement of class to a cage in a zoo. “But I keep hoping that someday I’ll find that it’s all a bad dream”, he muses. The rat race never ends; “they might as well have sold me too”. If the lamentations of the American labourer professed in Stud’s Terkel’s Working were put to music and collated into an LP, it’d be “Snowblind Traveler”.