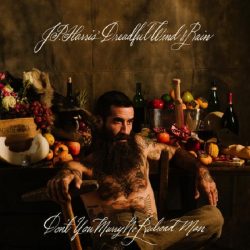

Folk perfection from JP Harris and Chance McCoy

Just when you think you know JP Harris as the real-deal no bullshit slightly Outlaw Country musician with the voice that has been more than lived in he goes and throws you a curved ball. Earlier this year it was the Q-Conspiracy mocking single ‘Take Off Your Tinfoil Hat‘, and now it is this present album which reshapes and represents JP Harris as a natural reinterpretor of traditional song. It sounds as if he was born to record this album – and indeed he’s been working up to it for most of his life because before he became the darlin’ of Outlaw he was a regular at fiddle meets and stringband contest. On ‘Don’t You Marry No Railroad Man‘ he cedes the fiddle duties to Chance McCoy, but not only does JP Harris add the banjo parts he built the fretless banjo he’s playing.

Just when you think you know JP Harris as the real-deal no bullshit slightly Outlaw Country musician with the voice that has been more than lived in he goes and throws you a curved ball. Earlier this year it was the Q-Conspiracy mocking single ‘Take Off Your Tinfoil Hat‘, and now it is this present album which reshapes and represents JP Harris as a natural reinterpretor of traditional song. It sounds as if he was born to record this album – and indeed he’s been working up to it for most of his life because before he became the darlin’ of Outlaw he was a regular at fiddle meets and stringband contest. On ‘Don’t You Marry No Railroad Man‘ he cedes the fiddle duties to Chance McCoy, but not only does JP Harris add the banjo parts he built the fretless banjo he’s playing.

That weather beaten voice and the haunting combination of banjo and fiddle is to the fore from the start with a rendition of ‘House Carpenter‘ that brings out every unearthly and spectral element of a song that is rich in unfaithful lovers, tricksters and eternal sin that is not forgiven. It is a song that has so many layers to it, one of which is that sense of dancing with the devil and Harris and McCoy shine a dark light on that element – it’s spine shivers inspiring. Not everything is as serious – ‘Closer to the Mill (Going to California)’ jounces along at a fine pace as little knots of wisdom are thrown out in a random scattergun way “well it may sound funny but as sure as I sing if you want some money you got to sell something.” It’s the complete opposite of a nonsense song: everything is undeniably true but the difficulty is seeing te connection, but even that quandary is resolved “there’s a little secret in the words that I sing – when it comes to lovin’ you take what you bring.”

Fiddle comes to the fore on the tragic sounding but ultimately uplifting ‘Little Carpenter‘, which has a young woman turning away suitors in favour of her true love, the carpenter who shares all he earns with her. The punchline here is that there is no punchline – no-one is unfaithful, no-one gets murdered . The same can’t be said for ‘Wild Bill Jones‘ or ‘Otto Wood‘, very different sounding tales of wild young men – the first very much banjo led whilst the latter is fiddle and banjo at a dancing speed – but both are destined for a bad end. There are more lives that lead only to sorrow in the well known ‘Barbry Ellen‘, with unrequited love and a haughty demeanour leading inexorably to a double grave. It’s a superb version – as is every recording on this album which excels in conveying the key features of each song and thereby showing just why they have continued to be sung for so long. Some are regular features of many repertoires, and some are less familiar but whichever they are they are given the dutiful reverence they deserve through being played and sung as if they matter – because they really do.