All the world on a piece of paper.

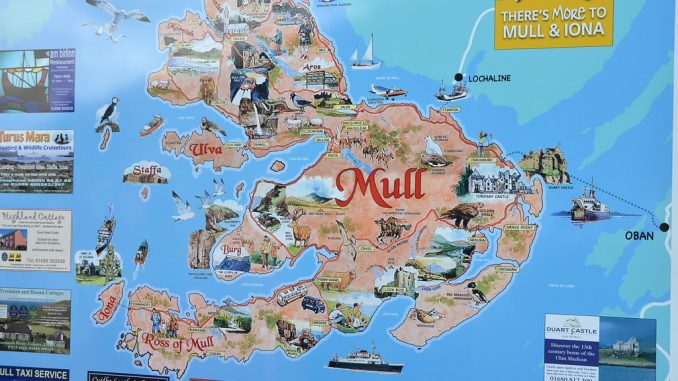

A map is a thing of beauty and that’s why I’ve got several on my walls. There’s a 1947 Bartholomew map of The Lakes (so different from the OS maps of today and to be fair the clarity is much refined in today’s offerings even if the colours are more attractive in the older version). I also have a lovely painted map, by one Ken Lochhead, of the west coast of Scotland centring on Mull but covering Argyll and Lochaber. Finally, there’s another hand-painted chart of the wrecks off the Farne Islands – and there were a lot. That combines the sea and the land so it’s a good example of the two formats. I’ve also got a map of Westmoreland (as it was before the vandals struck) in the style of Alfred Wainwright, that’s waiting to find some wall space. If you have seen his guide books you will understand the exquisite nature of the penmanship.

Just like good songs maps tell stories and just like the best songs and stories they sometimes take a little figuring out and explaining before they reveal all their secrets – that’s fine by me and there’s always a key to help the reader. There are some mistakes even on OS maps and sometimes there can be a little secret satisfaction in finding them – perhaps the forest that’s no longer there or twice as big as it was. Of course, you can sometimes just plain get lost.

Maps have their own histories and stories. They range from the bizarre early projections of an imagined earth – with monsters lurking in some uncharted locality – to the different scales, penmanship, colouration and printing of modern maps. It’s a miracle of printing that so much detail can be squeezed into such a small area and there’s a wonderful range of choice given there are a number of different scales depending on your intended usage. Consequently, you can view a whole area or just the little area you are standing on. I’ve never seen anything on a screen that can really match that.

Maps can take you anywhere you fancy whilst your feet never move and as much as anything allow the mind to wander and make its own images. I can look at a map of Mull and see pretty much the whole coast in my mind’s eye (having also physically seen most of it). That single track road alongside Loch na Keal at the foot of Ben More where you can park up on the flat area that leads down to the sea and enjoy the right to camp anywhere reasonable. You can look out over the island of Inch Kenneth and wonder what the Mitford’s actually did there. You can look up at Ben More and picture the ridge that goes up to the left after turning right at A’Chioch. It’s 966 metres above sea level – which was your starting point – the map tells you so and there’s no equivocation in a figure that specific. You might prefer the slightly easier route that goes up the right side or trek up the back from Loch Ba. Any way up the maps there to help you. On a clear day when you are at the summit, you can look seaward to the Treshnish Islands and further out to Coll and Tiree and if the sea is calm and the sunset right it’s beautiful enough to take away what’s left of your breath. You may just linger there for longer than is really necessary. You might also look back east across Loch Ba toward Craignure and the other side of the Island and on to the mainland.

Back below, as the map skirts the shores below Bearraich there are caves galore, waterfalls and, ‘The Wilderness’. Perhaps they just ran out of names but if that doesn’t entice you – what would? There’s a fossil tree and natural arches, there are sheep pens and something marked as a ladder – which I think is exactly what it says so you can view that Fossil tree. There are cairns – what for and who by? Certainly, they are not the guiding accumulations of passing walkers and I don’t think they mark stationary terriers either.

All of this is only a small corner of a small island – but you have a picture of it all – it’s called a map, beautiful in itself but wonderful in what it conjures up.

I don’t own any charts (they are not cheap) but they hold an equal fascination and have helped me and others fathom our way around the coast of Mull and much of North West Scotland in what, so far, has been safety. You can cross from Oban to Mull and discover that rough water and overfalls lie off the end of Lismore by the lighthouse. You can calculate at what state of the tide you would like to get there (there’s another thing – tide tables – but they are a utilitarian device not a thing of beauty). You can calculate whether that tide will help you get there or not – will it shoot you down the Sound between the island and the mainland or make it a slog out of all proportion. Your imagination can’t help but be intrigued by the Armada wreck off from Duart castle as well as pondering some of the strange diving experiences recorded there. What is going on in that water?

You can plan a trip around Ulva and Gometra on the western side of the island and ponder whether or not it’s safe to head out to Staffa. What waits for you there in an area of water notorious for bad weather? What lies off and around those headlands? A submarine exercise area – a firing range. Or is it the ‘dangerous tidal streams’ such as those that pass between North Jura and South Scarba heading westward into ‘The Great Race’ with kilometres of dangerous and difficult water beyond? On the biggest spring tides, the water will travel at 8.5 knots, more than twice as fast as you can paddle a kayak and it’s all kicked into a frenzy by undersea topography akin to a mountain range which creates a whirlpool, the third largest in the world. From 29 to 70 metres – it’s telling you just how deep and how shallow the seabed becomes – and that water has to go somewhere. One thing it doesn’t tell you is that the waves can reach 30 feet high (for that you need the coastal pilot but that’s another story). If the weather is blowing hard from the west then you have a sea that even George Clooney might reconsider. It’s called Corryvreckan and it nearly did for George Orwell.

Those innocuous little arrows on the chart – count the feathers and they will tell you how strong the tide will be. Those little wavelike things that look like happy emojis – they tell you where land meets water and in the shallows create a rough passage. And yet, time it right on the right day and it will be pancake flat. All of which indicates why seamanship is an art to be much admired and only acquired after years of experience.

For all that no one can readily tell me why a chart is a chart and a map is a map when essentially they are the same thing. Well, the American National Ocean Service tells us this – even if it is a little prosaic.

‘A nautical chart represents hydrographic data, providing very detailed information on water depths, shoreline, tide predictions, obstructions to navigation such as rocks and shipwrecks, and navigational aids.

The term “map,” on the other hand, emphasizes landforms and encompasses various geographic and cartographic products. Some examples of maps might be road maps or atlases, or city plans. A map usually represents topographical information.

A chart is used by mariners to plot courses through open bodies of water as well as in highly trafficked areas. Because of its critical importance in promoting safe navigation, the nautical chart has a certain level of legal standing and authority. A map, on the other hand, is a reference guide showing predetermined routes like roads and highways.

Nautical charts provide detailed information on hidden dangers to navigation. Maps provide no information of the condition of a road’.

Well – now we know – even if it doesn’t explain the romance of it all.

Found your site looking for information on ‘Morganway’ Saw them at Cropredy – The best band I have seen in years!

Also Love Scotland and West Coast ni partivular if it wasn’t for the deadly midge.