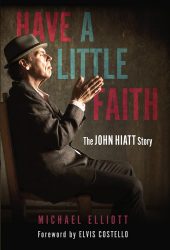

A long overdue, in-depth biography of one of Americana’s most enigmatic characters.

Singer-songwriter John Hiatt has long deserved, among many other accolades and tributes, to have a proper biography written about his complex life and career. Thanks to author Michael Elliott’s efforts and extensive research, while the Grammys have yet to get on board, a concise and well-written biography can be checked off that list.

Singer-songwriter John Hiatt has long deserved, among many other accolades and tributes, to have a proper biography written about his complex life and career. Thanks to author Michael Elliott’s efforts and extensive research, while the Grammys have yet to get on board, a concise and well-written biography can be checked off that list.

‘Have a Little Faith’’s introduction by Elvis Costello is affectionate but ends up telling the reader more about EC than about Hiatt. It makes sense that Costello was asked to write it, since Hiatt was referred to and marketed as “the American Elvis Costello” during his underrated Angry Young Man years, but surely there are better anecdotes he could have shared. The same could be said of Hiatt’s own input. He is notoriously private, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that his extensive interviews fill in a few blanks but don’t illuminate the events of his life or what was going on in his mind.

Elliott researched several generations of Hiatt’s genealogy, back to his English Quaker ancestors who emigrated to the American colonies and eventually made their way to the Midwest before the Civil War. Elliott’s research and Hiatt’s roots go so deep that during the first chapter I discovered that the tiny old Quaker cemetery I walk my dogs past nearly every day contains the graves of Hiatt’s great-great-grandparents.

Hiatt grew up in a solid middle-class Catholic family on the northside of Indianapolis. It was an outwardly stable family but plagued by dysfunction: gambling addiction, financial insecurity, sexual abuse, his father’s crippling morbid obesity and early death, and his older brother’s suicide. Music and alcohol became the means of escape for the shy, traumatized, socially awkward, chubby kid who had previously only lost himself in auto racing. However, the Sixties were an unfortunate time to be a music-mad white teenager in a sedate, conservative, stubbornly racially segregated city. Elliott’s description of the amusing scene of Hiatt’s mother tracking him down at a bohemian coffeehouse (probably after dark) and dragging him out mid-performance sails over the fact that it was on Indiana Avenue downtown, a traditionally black neighborhood once lined with jazz clubs but in decline by the late ‘60s.

From the moment John Hiatt moved to Nashville as an 18-year-old high school dropout and began his career with Tree International Publishing, he impressed people with his talent, “raspy howl,” and work ethic, first showcasing his songs at small venues like Exit/In. Ry Cooder tells a story that illustrates Hiatt’s seemingly effortless songwriting ability: he dropped by Hiatt’s house one day to ask for help on the song ‘Borderline,’ playing what he had up to that point through the bathroom window, with Hiatt writing the chorus on the spot while shaving at the sink.

As one of the godfathers of Americana, if Hiatt’s music became better known through other artists recording his songs rather than his own albums, it wasn’t for lack of trying on the part of fans and his network of friends in the music business. Norbert Putnam says, “John’s albums were never promoted by labels the way they should have been.” Elliott provides story after story of fellow songwriters, producers, managers, session musicians, music publishers, booking agents, and venue owners who simply like John Hiatt and will do anything to help him personally and professionally. Following his second wife’s suicide, friends stepped up to help him and his 1-year-old daughter Lily move thousands of miles across the country to start a new life in Tennessee. He is by all accounts such a down-to-earth, funny, affable, and unpretentious person that people enjoy working with him and being around him — and did so long before he was in recovery from alcoholism.

Like Paul McCartney, another artist who can give a long interview while not revealing much about himself, Hiatt eagerly embraced a quiet life of stability and domesticity on a farm in Tennessee with his wife Nancy and three children while consistently putting out excellent work. It’s a challenge to write a biography of a genuinely good person, however much tragedy and drama have insistently gatecrashed that person’s life. It’s always easier to find more colorful stories about a complete bastard. Elliott does an admirable job of capturing a redemptive thread in Hiatt’s life, sobriety, and personal growth, even while writing about multiple recording sessions and subsequent tours from the ‘80s to the present where nothing really went wrong.

The most interesting parts of the book are the glimpses into Hiatt’s progress as a songwriter, constantly changing how he works but remaining a disarming ‘everyman’ to whom so many listeners can relate. One can’t help putting the book down to listen to his songs as they come up in the story. Elliott perfectly describes him as a writer: “Hiatt comes from the Raymond Carver school of dirty realism coupled with a wicked sense of humor, used sometimes to lighten the mood of the darkest subjects.”

You’ve made me want to read that Kimberley!

Come back after you read it and tell us what you think!