With a guitar in good hands, there’s still a place for old-time folk and country blues, contemporized for the 21st century.

On a sunny April afternoon, the release date for his new album, “Little Sun,” Charlie Parr and Americana UK’s Dean Nardi sat on a picnic bench behind Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, NC, shooting the light breeze that was welcome on a hot day. Parr spoke of listening to his father’s record collection and borrowing LPs from the library in the small working-class town of Austin, Minnesota, He also told of being a young man in Minneapolis, hanging out with Spider John Koerner and Tony Glover, absorbing how they played like a tree absorbs carbon dioxide and releases fresh oxygen for his music to breathe. When I confessed to knowing of Spider John but not Glover, Parr laughed heartily and said, “Well, you’re in for a treat today.”

Charlie Parr is a terrific folk and country blues singer/songwriter who is appreciated by an increasing number of steadfastly devoted fans. His vast knowledge and reverence of old-time music has undoubtedly informed his own songwriting, earning him respect from both his peers and those who know great music when they hear it.

Mance Lipscomb and Mississippi John Hurt were players he admired and tried learning their style. Pouring through volumes of the Harry Smith Anthology introduced him to other guitar players and influenced his desire to one day give up his day job to make records and become a full-time troubadour. It’s no wonder his approach to music is novelistic, singing about characters stuck on the barbed wire of life. Listening to Parr tell tales of being on the road more than 200 days a year brought to mind a book by the author John Steinbeck titled “Travels with Charley.” That Charley was a dog who accompanied Steinbeck on his journey throughout America. It makes you wonder what it would be like to tag along with Parr, as he likes to say, driving around the country, playing music and looking at stuff everywhere.

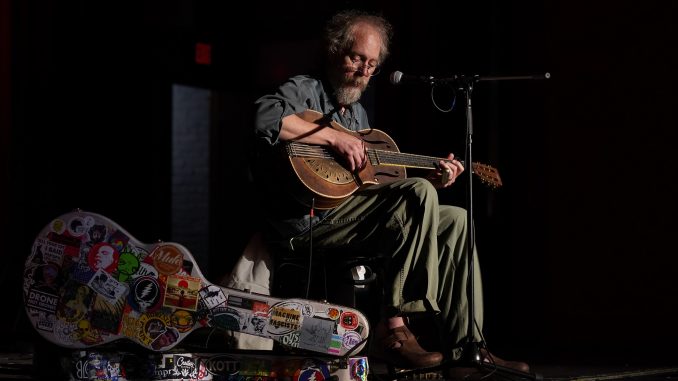

On stage, just him and his guitar, a lone chair and a mic, Parr is a master storyteller who projects an appearance of the common man, simply dressed in a flannel shirt, plain jeans and work boots. Off the stage, he strives to simplify life and be grateful for what it has to offer. He expresses gratitude for having been able to record 18 albums from ‘Criminals & Sinners’ in 2002 to the excellent ‘Last of the Better Days Ahead’ in 2021. His 19th is “Little Sun,” honoring Tony Glover’s nickname.

There’s a certain respect that comes with such an impressive achievement, releasing 19 studio albums in 22 years. Some of the earlier ones are out of print. On eBay they are, to put it mildly, very pricey.

I got connected with a company that put all the old albums up on streaming services because I’d decided not to reissue any of them physically. Times are changing and I have to learn to keep up.

‘Little Sun’ is different in that you have a band rather than playing solo or with sparse accompaniment as on the majority of your albums. What prompted the change?

Well, I intended to do this (band) one record ago. I’d been wanting to try playing with a band for a while, but on my previous record, ‘The Last of the Better Days Ahead,” the pandemic was going on making getting people together impossible. I talked with Tucker Martine, who produced the new record, and he was anxious to get started. It was going to be great. But it just didn’t feel like the right time. Also, with those songs, there wasn’t much room for anybody else, so I recorded alone like I usually do and was happy with the result. Then, when the time came to do another record, I thought we’d try again because the songs had a little more air in them, room for someone else. Tucker and I had a great talk and I decided to go ahead out to Portland (Oregon) and see what it was like.

Well, I intended to do this (band) one record ago. I’d been wanting to try playing with a band for a while, but on my previous record, ‘The Last of the Better Days Ahead,” the pandemic was going on making getting people together impossible. I talked with Tucker Martine, who produced the new record, and he was anxious to get started. It was going to be great. But it just didn’t feel like the right time. Also, with those songs, there wasn’t much room for anybody else, so I recorded alone like I usually do and was happy with the result. Then, when the time came to do another record, I thought we’d try again because the songs had a little more air in them, room for someone else. Tucker and I had a great talk and I decided to go ahead out to Portland (Oregon) and see what it was like.

How did that turn out for you, playing with a band?

It was fun, comfortable for me because we sat down and played the songs like I usually would. Then we’d do them again and talk about it, and that was different because I usually don’t hang around studios. I get there, play my songs, pack up and leave.

Marisa Anderson played guitar on the new record. Her own albums are gaining popularity. There is a minimalist or cinematic approach to her music, experimental in nature. It’s quite different from your style. How did she happen to play on your album?

Actually, she’s been one of my favorite guitar players for a long time. I just like her music. There are a few guitarists in the world today who are doing a kind of deconstruction of traditional guitar stuff. You can’t always just recycle John Fahey over and over again. Something new has to happen, and I think it’s Marisa, Bill Orcutt, Chuck Johnson and Laurel Premo who are coming up and adding their own atmosphere to an instrument that I felt really benefited from an extra shot in the arm (not another vaccination, folks). Ever since I heard Marisa’s first record, I just wanted to have that sound on my record, so when she came in it was just, well, heaven listening to her react to my songs. She’s classically trained and knows the fretboard as good as any guitar player you could name. It was important the way she took care of my songs.

One of the songs on the new record is ‘Portland Avenue,’ which seems to portray a sense of loss, whether individually or in America. What are you saying in that song?

I guess I wasn’t really thinking of it in a national way. There are several different versions of that song. The first few versions were about something less physical, like Alzheimer’s when people disappear that have been sitting right in front of you. My mother is struggling with problems from dementia. I can’t even imagine what that must feel like. So, it’s trying to come to terms with people that have been in your life and are still in your life but parts of them are fading away. You know, people come and go all the time and you’re left to kind of deal with what remains of them.

Why was ‘Little Sun’ chosen as the title song for the new album?

Well, I wrote the song for Tony Glover. I’d been thinking about him. So, you go back in time to the early ‘60’s when Koerner and Glover had a folk blues trio with Dave Ray. (I cut in to say Spider John Koerner.) Yeah, “Spider” John Koerner, Dave “Snaker” Ray and Tony Glover, who was called “Little Sun.” I came to Minneapolis in the ‘80s and moved to the Right Bank. Those guys were still alive and playing. Now the only guy still living is Spider John. (Sadly Spider John Koerner passed away on May 18th, Ed.)

What effect did those three have on your career? Especially Tony Glover, since you honoured him with the album’s title.

I don’t know if there was a bigger influence on me personally. On Thursday nights I could go downtown to the Times bar and see Glover and Ray playing blues, and Tony was a phenomenal harmonica player. He wrote an instruction book for harmonica playing called “Blues Harp.” He was the sweetest dude, you know, generous with his time. When I finally got the courage to go meet him, talk to him, Tony wasn’t the kind of person that felt like other musicians were in competition with him, ‘cause that’s fake. When you get into the depths of music and look behind the curtain of the music business, you realize that kind of competition is fake. He understood that really well. He was supportive and made me feel like what I was doing had some kind of relevance, some value, and that I should just keep doing it no matter what. That meant the world to me and still does. Unfortunately, the man passed away too early but before he died, he asked that I be one of the two people who would play at his memorial. That was the honour of my life. It was just me and Spider John, and that was the last time he played in public, around five years ago. Afterwards, John gave me his guitar and stopped. That’s been really important for me, that whole West Bank music scene, getting to see Tony play every Thursday. On Fridays I’d go to the 400 bar to see Willie Murphy play solo barrelhouse piano. That was just mind-bending when Tony would come down and play harmonica with Willie. Sundays Spider John played solo sets at the Viking bar. I was soaking up that scene, which started around 1962 or ‘61, whatever, and it still kind of informs my playing. I wrote that song while thinking about Tony and it felt right.

Do you think the music was better or more exciting back then?

Anytime you show up anywhere somebody’s going to tell you that you should have been there back when. That’s just natural. But I think right now is probably as good a time for music as any. Maybe it’s the best time, I mean, we’ve all got access to so much more than ever before. The only frustrating part is you just can’t get to it all. When I really fell hard for music, say around 1976 when I was 10, well, the little town I grew up in didn’t have any record stores. The only way to hear music was my dad’s record collection. My sister was into music, too, so I had those two to feed off of. Then there was the library in Austin (Minnesota) that had an amazing collection of LPs on the second floor, all the Folkways records including the Harry Smith stuff. We’d scour through the Goodwill and Salvation Army looking for records. Now with a phone, everything in the world is available in my pocket. Is it better or worse? It certainly is a whole lot easier.

‘Bearhead Lake’ sounds like it could be your ‘Walden Pond’ song. Tell me how you see it.

‘Walden Pond’ is one of my favourite books. I don’t know, but maybe. Living in Minnesota there’s a lot of opportunities to just get away from the city, and in a very short period of time you’re in the woods, especially in Duluth. You can just walk down the street and there’s cricks that cut through Duluth, and they’ve left them so that when you get down to where the crick is you feel like you’re a hundred miles away from anything. You can barely hear the traffic. I’m grateful to have had access to the outdoors. Bearhead Lake is up near Ely, Minnesota, which is the gateway to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, a giant nature sanctuary. It’s like a primitive, undeveloped state park. You sure wouldn’t bring a 50-foot RV there, though.

I hear similarities in ‘Pale Fire’ and ‘Bearhead Lake.’ Would that be a fair assessment?

It would. They were actually the same song at one point, one giant song that was all mixed up, super messy, so I split them into two. The melody for ‘Pale Fire’ was going to be something else but after splitting them, I ended up with two sets of lyrics that resembled each other. It turned out to be kind of a reincarnation song where death comes at the end of the day, life comes in the morning.

‘Boombox’ is more of an upbeat track. One might say atypical for you?

Probably, for sure. It was nice for a change to write something a little more upbeat, although maybe it’s not all that upbeat. It’s a song about leaving people alone. There’s no skin in the game to, for example, bother people about the way they dance. That’s subjective. The song is a reaction to people trying to control other people over stuff not fundamental to our survival, like the way you dress, the way you wear your hair, the way you dance, the way you vote. There’s a long list of those kind of things. I want my kids to be comfortable in the world, be able to express themselves without fear of conformists bothering them all the time. So, yeah, the song’s a reaction to all that, which isn’t upbeat or happy, but I think we managed to get to a place with the tempo of the song that makes it feel bouncy and happy. It can be an uplifting message. I’m glad because I struggle trying to make music that’s uplifting. I guess that’s just my nature.

‘Stray’ sounds as if it could have been on one of your other records instead of the one with a band.

That one is part of a bunch of songs with a theme I come back to over and over throughout all the records because it’s important, about people living on the margins, displaced, struggling to get along. ‘Stray’ is a continuation of that theme. Maybe it’s just me wrestling with the same knot, trying to figure out a way to say something relevant about the issue. I don’t think I’ve gotten it down yet. It’s really declamatory, almost accusatory. I don’t want to come off as aggressive or hostile, so I guess I should keep working on it.

Since ‘Little Sun’ is a band record will you be touring with a band?

No. Tonight it’s just me. I’ll only be doing one band show and that’s in Minneapolis. It’s already a bear to put together because I’m not a good organizer. I haven’t had a job for 22 years and have been traveling alone ever since. Putting together a band is too much to ask. All these songs on the record, even though it’s a band record, started as solos. It’s just natural, the way it’s supposed to be.

Which is your guitar of choice presently?

My main guitar is a resonator made by the Mule Resonator Company in Michigan. As for the technical part of it, well …. the two guitars I use are both resonators. One guitar looks like a National but it’s actually a Tricone. It’s got three resonator cones instead of just one, but it’s in a single cone body. National makes a Tricone but they’re in a special tri-plate body, which makes a difference in the sound. I have no idea why but when I played Mule’s version, I just fell in love with that sound. It’s got aspects of both kinds of tones. Tonight, I have two Mule Resonators, one with a metal body and the other a wood body. They sound very different but also really similar if that makes sense. Probably doesn’t.

I know a little about playing guitar and last night looked at one of your videos. Not to split hairs, but your thumb was always on the bass and the finger-picking appeared to be Travis-style but it wasn’t.

Yeah, it’s definitely related to Travis. When I was learning to play guitar, I was listening to Mance Lipscomb. His was the one record in my dad’s collection that had that type of picking. Mance did kind of a corrupted version of Travis. His thumb was picking alternate bass, but he used one finger instead of two fingers to pick out the melody. After I got deeper into the style, I found a bunch of guitar players fell into this category, like Reverend Gary Davis who plays both ragtime and country blues stuffed together. Bukka White is another. It’s a weird kind of not this or that way of playing.

Isn’t there a little stride piano in your playing?

I love stride piano and listen to a lot of piano players. Gary Davis came at the guitar like a piano because he listened to ragtime piano players. So, yeah, it’s in there.

When we met today, you were sitting here reading a book. Very little equipment to move in, no band to coordinate, short soundcheck, nobody taking up your time, well … except me. I get the impression that it’s important for you to exist within music on your own terms.

My philosophy is don’t do anything I don’t want to do. I’ve got a record label but they work for me. That’s easy to forget sometimes. I’ve got a lot of help that I’m grateful for, but at the end of the day this is my ride. I want to do stuff in a certain … well, it’s more accurate to say I don’t want to do stuff in a certain way. I’m inherently very, very lazy. I like not having a job. I just get up there and play my music. It means everything, being part of something that’s bigger than me.

‘Last of the Better Days Ahead’ has a recurring theme: the pain of looking backward at all the woulda coulda shouldas or looking ahead at what might go wrong instead of staying in the moment. People have a habit of saying: Better days are coming or my better days are behind me but never these are the better days, right now.

My mother is 95 and she’s got some dementia happening and Parkinson’s, too. When she got diagnosed with Parkinson’s, I took her on tour because she was scared that she was going to go down fast. She wanted to see the Grand Tetons, had never seen them before. I happened to be going right through there so I said pack your stuff and get in the van. We even took my kids because by then I’d been divorced. So off we went on the road. It was so much fun, having two weeks of all this amazing conversation. She was born in 1928 and her family was dirt poor, farmers but didn’t have a farm. They were hired hands in southern Minnesota. During that trip she said: “This is a weird time in my life. I feel like I’m in a rowboat but don’t have any oars. I’m just in the river slowly circling around and at times I can see the past like it just happened. And at other times it just fades away and I can’t remember anything. All I can see is this fuzzy future part.” That was a really interesting thing to say, and it stuck in my head. Like it’s real macabre but interesting. She also said recently that she’s at a point in her life where she feels like she’s all of the ages at once. Time is different to her now and she spends days vividly remembering what it was like to be seven.

It seems that for your mother the past is gone and the future is no longer filled with fear because her life is in the present, being present, even if the present could be at any point in time. Is this something that connects with you?

That’s something she’s gotten good at, and I feel like I’m getting better at it. Being on tour all the time keeps you in the moment in like a forcible way because I’m driving a lot and I want to be in one piece when I get to the next place, so I’m constantly thinking about what’s happening right now. I don’t listen to much when I’m driving, only ambient music or nothing, just to stay focused. That’s actually helped me in a lot of other ways, to slow down and take it all in. I like going slow. It’s the best way for me to live my life, to play my music, being in the flow.